I found it

I stood there for a moment, admiring what I had pasted on the back bumper of my dad’s car: a vivid yellow background with bold black block letters practically shouting, “I found it!” The strategy was ingenious; people passing by would glance at it, raise their eyebrows in curious intrigue, and inquire, “What did you find?”—a perfect segue into a conversation about how I had found Jesus. The goal was clear: to save the lost and lead people to conversion. The weekend seminar had invigorated me. I was on a mission.

With the bumper sticker firmly in place, my next task loomed before me: call every person in the city and ignite the same curiosity by leading with the line, “I found it!” I was a young, naive teenager. I mustered the courage, but I was left feeling deflated after only three attempts.

The first call was to an older gentleman who answered politely but quickly expressed disinterest. The second call took me all the way to the end of the questionnaire, where a conversion was supposed to occur, but the woman on the line confessed she was already a Christian. For the third call, the moment the phone connected, an irritated voice erupted with a few choice words, “I’m sick of Christians pushing their beliefs on me!” he roared, shutting down the conversation with an abrupt hang-up.

I sat on the bed in stunned silence with the phone resting uselessly in my hand. The failsafe strategy I had envisioned crumbled before me; it was nothing as I had imagined. A frosty wave of realization washed over me: I had zero endurance for a mission that evoked such resentment. What had once sparkled with brilliance now felt like a misguided endeavour. Feeling the weight of my disillusionment, I trudged outside and peeled the bright yellow sticker off my dad’s car. I wasn’t angry—just caught off guard, as if the air had been abruptly let out of my worldview.

Not long ago, after visiting a church to share my experiences in Congo, a woman approached me excitedly to share her own Congo experience. She had recently taken a two-week trip to share her faith and ended up converting over thirty people. She simply went door to door with a translator and shared her testimony. She confronted me and asked who I had converted. I hesitated before answering, “No one.”

In that moment, my mind hadn’t stumbled on my own belief system; instead, I found myself pondering this woman’s worldview. It had been a familiar one to me, and I wondered if there was any value left in it, or if it had withered into a hollow ritual—a lifeless adherence to religious duty devoid of genuine meaning?

As I reflected on my own obligatory behaviours as a Christian, an old cartoon image from the Moody Institute flashed into my mind. It portrayed a rowboat tossed about in rough waters, with concerned people inside risking their lives to reach out and save the desperate, drowning victims still in the water. The caption read, “I don’t find any place where God says that the world is to grow better and better…I look upon this world as a wrecked vessel. God has given me a lifeboat and said to me, ‘Moody, save all you can.’”1

I must admit, Moody had a rather bleak outlook on the human experience. The idea that we are all on board a sinking Titanic is foreboding. Is our only hope for salvation truly to find a lifeboat amidst the chaos? What if I don’t see one? And if I do find it, why would I hesitate to climb in? So many questions swirling in my mind. Is this really the message conveyed in the Bible?

Shûb – to return to the path

The Jewish Torah is perhaps the most fitting starting point for understanding this topic, and it says little about rescuing the unsaved or seeking to convert them. The concept of conversion isn’t inherently Jewish. Instead, the Jewish approach focuses on the notion of returning rather than converting. Allow me to explain what I mean.

Every once in a while, my computer gets sluggish, and the only solution is to turn it off and then back on—essentially performing a simple computer reset. In the same way, at the end of every Jewish year, there is a reset. This period begins with a month of self-examination and reflection known as the Month of Elul. Following this, Rosh Hashanah marks the beginning of the Jewish new year, which is ushered in by the Ten Days of Repentance, culminating in Yom Kippur, the Sabbath of Atonement. The purpose of this time is to realign the community back onto the correct spiritual path.

Within the first ten days of the year, there is another Sabbath which has a unique name: Shabbat Shuvah, or the Sabbath of Returning. The root word in ‘shuvah’ is derived from the Hebrew word ‘shuv’ or ‘shûb’ (שׁוּב), which was used by the prophet Hosea when he calls out to his people, urging, “Return (shûb), O Israel, to the Lord your God”.2 The word ‘shûb’ resonates deeply throughout the Old Testament (OT)3, appearing over 1050 times and in each instance conveying the same call to return. Moreover, the word ‘shûb’ serves as the root for the word ‘teshuvah’ (תְּשׁוּבָה), which is translated as repentance.4 Repentance is not merely an acknowledgement of wrongdoing; it embodies the profound act of stopping, turning around, and returning to the right path.

While the word ‘convert’ may seem similar, there is a subtle yet significant difference. Recently, I converted a wooden door I no longer needed into a table. The act of converting implies a profound change, a transition from one state to another, much like the transformation of a discarded door into a functional table.

As I worked on this project, I faced the challenge of ensuring precision. If my saw inadvertently strayed from the carefully marked line, I would have to pause, make the necessary adjustments to get back on track, or my project would fail. In this way, the term ‘shûb’ warns me that I have veered off the correct path and must return to it. Although ‘shûb’ is occasionally translated as ‘convert’56 in some OT translations, the context is always tied to restoration and the act of returning. It is interesting to note that the term ‘conversion’ is never used in the OT, presumably because it isn’t talking about one-time events but an ongoing act of returning.

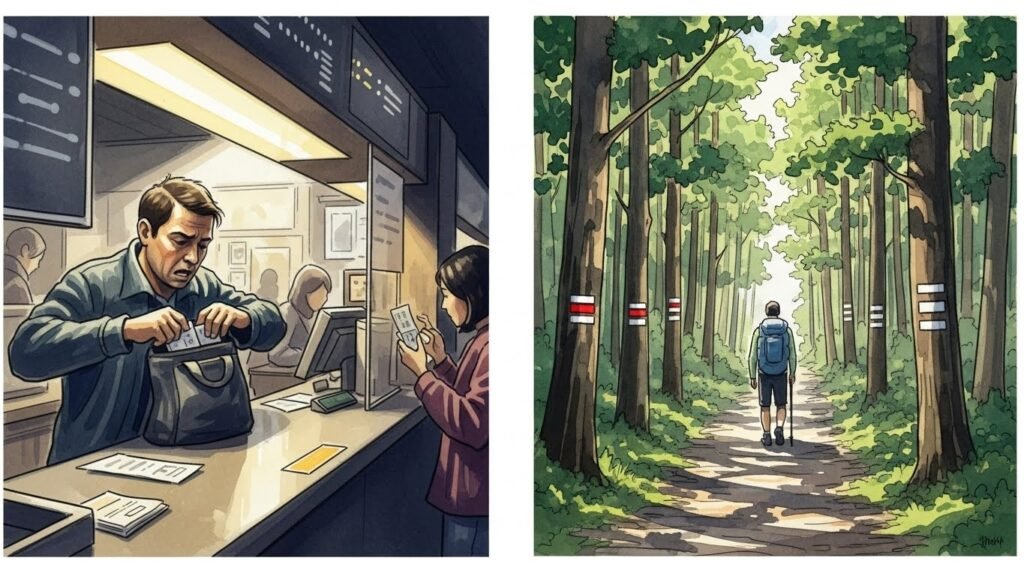

In my view, a more accurate translation of the word ‘shûb’ should capture how easily we can be distracted and veer off track. Life is a journey that requires a regular reset. The word ‘shûb’ should not be thought of as a lifeboat rescuing us in a storm, but as a guiding beacon or a trail marker, illuminating the path back to a Godly way of living.

It is crucial to understand that the Ancient Hebrew word ‘shûb’ does not imply anything like being awarded a ticket to the World Cup finals, a certificate of citizenship, or anything that indicates we finally made it in. Nor does it claim that everything will be fine once rescue has occurred and we are aboard Moody’s boat. Instead, the word ‘shûb’ focuses on the path we travel and our innate tendency to lose our way. Ironically, Moody’s boat will need ‘shûb’ to stay the course back to the port.

Metanoéō – an enlightening change of direction

Once the Ancient Greeks began to show interest in Jewish scripture, they faced the challenge of translating the Hebrew word ‘shûb.’ In their translation of the OT, known as the Septuagint, the Hebrew shûb is rendered in Ancient Greek as ‘epistréphō’ (ἐπιστρέφω), ‘metameleia’ (μεταμέλεια) and ‘metanoéō’ (μετανοέω). In English, these words are translated as ‘turn around,’ ‘turn back,’ ‘change,’ or ‘repent.’ Among these, ‘metanoéō’ is most commonly used and is best understood as ‘changing one’s mind,’ similar to the revelation experienced in a eureka moment or spiritual enlightenment.

Later, in the New Testament (NT), which was primarily written in Koine Greek, the same three words frequently appear. The term ‘metanoéō,’ the most common of them, is used over fifty times7 and is often translated into English as ‘repent.’

Interestingly, the word ‘convert’ also appears occasionally in English translations of the NT, though it is never used as a direct translation of ‘metanoéō.’ When ‘convert’ is used, it denotes a transition from one group to another, marking a milestone or pivotal moment in the early church’s growth.

Two notable conversion stories stand out in the NT: Saul’s conversion (Acts 9:1-17) and Lydia’s conversion in Philippi (Acts 16:11-15). Although these events are significant, it is noteworthy that the words ‘convert’ or ‘conversion’ are conspicuously absent from these accounts. This omission raises the question of whether the early Greek-speaking biblical authors considered conversion the primary objective of faith, or whether they placed greater emphasis on the ongoing journey of transformation described in the Jewish concept of ‘shûb.’

To convert or to begin a journey?

The concept of conversion presents a significant issue in the book of Acts. The narrative begins on the Day of Pentecost, when the early church was entirely Jewish. As the Gentiles began to embrace the teachings of Jesus, a question arose: did these Gentiles need to convert to Judaism? For these early Jews, becoming a practising Jew was a natural progression of following Jesus, who was, afterall, a Jew.

The early church faced a dilemma: Did following Jesus mean embarking on a journey that required a repentant attitude to remain aligned with his teachings? Or did it mean admission into a new community by becoming a Jew, which would involve adopting certain Jewish practices like circumcision? Paul was confident that following Jesus did not necessitate conversion into Judaism. For him, it was fundamentally about a change of heart.

Brothers, you know that some time ago God made a choice among you that the Gentiles might hear from my lips the message of the gospel and believe. God, who knows the heart, showed that he accepted them by giving the Holy Spirit to them, just as he did to us. He did not discriminate between us and them, for he purified their hearts by faith. Now then, why do you try to test God by putting on the necks of Gentiles a yoke that neither we nor our ancestors have been able to bear? No! We believe it is through the grace of our Lord Jesus that we are saved, just as they are.8

The primary concern of these Jesus-following Jews was rooted in their cultural identity. They insisted that the Jesus-following Gentiles abandon their Hellenistic cultural identity and embrace Jewish traditions and customs. However, Paul argued that following Jesus was not about enforcing cultural rules to ensure Christ-like behaviour; it was about an ongoing transformative journey that the ancient Hebrews called ‘shûb’—repentance. The objective was not one of conversion—converting Gentiles into Jews—but of restoration. He believed it was not the Jewish laws that would guide the new believers into a new and fulfilling way of living; it was the Holy Spirit.

At this juncture in history, the early church was primarily reliant on the Jewish scriptures for guidance. The removal of the necessity of conversion to Judaism represented a dramatic and unprecedented shift. Did this mean Paul was demoting the laws of the Torah? After all, these laws were well-established, accompanied by a strong tradition of practice. The suggestion to set aside these laws and rely on the Holy Spirit marked a radical change that was not yet fully understood or integrated into the life of the church.

Nevertheless, a dependence on the Holy Spirit continued to flourish throughout the early centuries of Christianity, as illustrated in Augustine’s writings, where he states,

“From here, each of us has the end of going home. We end in the place we are going to. So now then, here we all are, engaged in life’s pilgrimage, and we have an end we are moving toward. So where are we moving to? To our home country.”9

In an era without a canonized Bible, the early church fathers relied heavily on letters circulating among them or on a shared, albeit unwritten, understanding of what it meant to follow Jesus. In this formative time, they relied on the Holy Spirit to guide them on their journey of becoming.10

The distortion?

The Bible, as we know it today, came into existence around the time Emperor Constantine established the state church. For many, the creation of a state-supported church offered a sense of relief, but it also led to a distortion. The emphasis shifted away from a transformative journey of faith toward a fixation on the ultimate destination: absolving wrongdoing and securing eternal life as a reward for belief. It was less about the kingdom that has come and more about the kingdom still to come. Conversion became the church’s primary task, overshadowing the importance of a fulfilling journey in the here and now.

This distortion created ample opportunities for abuse by those wielding power. Despite the positive changes brought by the Reformation,1112 the emerging Protestant Church quickly aligned itself with the state to secure conversions. The alliance justified heavy-handed political control and even warfare. When this didn’t convert them, they enticed people with promises of a better future and eternal life. It became less and less about fostering genuine behavioural change. This same understanding of conversion—a ticket to a better afterlife—persists today in many evangelical congregations, albeit to a lesser degree of manipulation.

The early immigrants to America sought to escape the confines of the state church in Europe. They saw through the self-serving ambitions of those in power and viewed the European state churches as cold, controlling, and oppressive. They yearned for a more liberated and fulfilling expression of faith. For these immigrants, conversion was not merely a ritual but a profoundly personal and spiritual experience—a heartfelt transformation that represented a commitment to living a pious life, unmarred by the state’s interference.

This sentiment piety manifested during the 18th-century First Great Awakening. This revival emphasized the role of the Holy Spirit in the lives of believers. Even so, the focus on a clear and discernible conversion experience continued to hold sway. This trend continued into the 19th-century Second Great Awakening, which was characterized by passionate figures such as Charles Finney, Dwight L. Moody, Billy Sunday, and Billy Graham.

Amidst this revivalist fervour, the concept of the ‘anxious bench’ emerged—a practice where individuals moved by the preacher’s impassioned sermons were beckoned to come forward to the front of the church to receive salvation. This practice often relied on emotional manipulation, using persuasive rhetoric and stirring hymn melodies to sway the congregation.

“The whole of this is made to bear, with all the weight the preacher can put into it, on the question of coming to the anxious seat. Every effort is employed to shut up the conscience of the sinner to this issue; to make him feel that he must come or run the hazard of losing his soul.”13

Cautionary arguments

Today, among Evangelicals, conversion is the primary goal, and they support it with numerous Biblical passages. However, we should consider the cautionary guidance that comes from the same Bible.

First, conversion to follow Jesus is often confused with a conversion to a Christian culture. Just as the early church Jews struggled to separate their laws and customs from what was demanded by their newfound faith, we must ask ourselves if we truly recognize where our cultural practices end and a genuine change of heart begins. As Christians, we frequently impose demands for conversion—whether that be uttered with the lips or assumed in the mind. It would do us well to examine our motivations closely in this regard.

Secondly, if we are to follow the model in Scripture, we are invited into a journey of repentance. Scripture repeatedly emphasizes repentance or returning and suggests that it is something to revisit—perhaps daily. We are in the process of becoming Kingdom citizens. Both Hebrew and Greek imply that following Jesus or returning to God is less of an irreversible event and more of a journey of becoming. The image of a bridal ceremony is frequently used to convey this journey of repentance.

The theme of renewal is found in the Lord’s Prayer in the phrase, “Your Kingdom come.” The coming kingdom implies a process of returning to the Garden, which represents God’s established rule. The Book of Acts continues this narrative by telling the story of a messianic community so inspired by the story of Jesus Christ that they committed themselves to ‘Kingdom come’—a moral shift, a new virtue, or a redeemed manner of behaviour. It is not conversion that brings God’s kingdom; it is a new way of being.

During a recent trip to Iraq, I found it challenging to count the number of converts. However, I could count those who were on a journey. I met Muslims and Yezidis who were hesitant to identify themselves as converts but openly acknowledged that they were on a journey of repentance. Perhaps they were returning—they were becoming.

Finally, the Apostle Paul was content to let the Holy Spirit guide the Gentiles into a new way of practising their faith. He understood the risks of the new believers Hellenising their faith, but chose to trust the Holy Spirit. Some situations remain ultimately beyond our control, and there is a precedent for allowing change to rest in the hands of the Spirit.

Our response?

While conversion and subsequent baptism are significant milestones—much like a wedding ceremony is an essential milestone in a marriage—the journey is often overlooked. We inevitably will veer off the path, prompting the need for ‘shûb’ —a returning. As a community, we might benefit from placing greater emphasis on our journeys. Perhaps we should dedicate more of our time and resources to creating safe spaces for understanding and engaging with one another.

We are often drawn to the idea of conversion because it defines a clear line between those who are in and those who are out. A journey, however, is not so black-and-white. Personally, I am not always certain when I’ve veered off path. I need the experience and input of others.

The community of believers is made up of people at different places along this journey. This diversity serves us well, and it is a key characteristic of the church that separates it from being merely a club. The interactions among diverse individuals in communion with one another, despite differing views and positions, make the path clearer.

When we approach this journey with humility, acknowledging that not everything can be explained by Dwight Moody’s lifeboat and admitting we may not have it all figured out, we recognize our need for regular resets—‘shûb.’

The good news is the promise of the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is at work within us, in our community, and in those who view the world differently, regardless of their position along the journey’s path. While conversion certainly implies commitment, and commitment is a good thing, how that commitment manifests is influenced by the Holy Spirit in our lives. Like Paul, we trust that the Holy Spirit is at work, shaping and drawing the entire world to Himself.

Questions of reflection

- How can we create safe spaces for honest dialogue and spiritual growth?

- What does returning look like in our daily lives and relationships with others?

- How do we support those who are have questions about their faith journey?

- How should we balance traditional practices like baptism with the ongoing journey of faith?

- What practical steps can we take to value and learn from our community’s diversity?

- Original reference not found. Frequently quoted as being said by Dwight L Moody in his sermons. Referenced in: Stanley N Gundry, Love Them In: The Proclamation Theology of DL Moody 1976, or Williams, The Life and Work of Dwight L Moody: The great evangelist of the 19th century p149 ↩︎

- Hosea 14:2 ↩︎

- Here are some examples: (1) He said to his servants, ‘Stay here with the donkey while I and the boy go over there. We will worship and then we will come back to you (shûb).’ (Gen 22:5 NIV) – the physical motion of returning; (2) Say to them, ‘This is what the Lord says: “‘When people fall down, do they not get up? When someone turns away, do they not return (shûb)? (Jeremiah 8:4 NIV) – turning away from a destructive life (sin) and back to God; (3) Now these are the people of the province who came up (shûb) from the captivity of the exiles (Ezra 2:1 NIV) – a return from exile to fulfill a covenant. ↩︎

- Here are some examples of shûb translated as repentance: (1) When you and your children return (shûb) to the Lord your God and obey him with all your heart and with all your soul according to everything I command you today, then the Lord your God will restore (shûb) your fortunes and have compassion on you and gather you again (shûb) from all the nations where he scattered you. (Deut 30:2-3 NIV); (2) If they turn back to you (shûb) with all their heart and soul in the land of their enemies who took them captive, and pray to you toward the land you gave their ancestors, toward the city you have chosen and the temple I have built for your Name (I Kings 8:48 NIV); (3) Otherwise they might see with their eyes, hear with their ears, understand with their hearts, and turn (shûb) and be healed (Isaiah 6:10 NIV)

↩︎ - Here are some examples of shûb translated as convert: (1) The law of the Lord is perfect, converting (shûb) the soul; The testimony of the Lord is sure, making wise the simple; (Psalm 19:7 NKJV) – also translated as ‘restoring the soul’; (2) Then I will teach transgressors Your ways, And sinners shall be converted (shûb) to You. (Psalm 51:13 NKJV) – also translated as ‘return to you’; (3) Zion shall be redeemed with justice, and her converts (shûb) with righteousness. (Isaiah 1:27 ASV) – also translated as ‘her restored ones’ ↩︎

- In certain versions, like the NIV, the word convert never is used. ↩︎

- Here are some examples of the use of metanoéō in the NT: (1) Repent (metanoéō) , for the Kingdom of God has come near. (Matt 3:2 NIV) – call to turn from sin; (2) The Kingdom of God has come near. Repent (metanoéō) and believe the good news! (Mark 1:15 NIV) – call to acknowledge one’s sin and turn to faith in him; (3) Repent (metanoéō) and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins. (Acts 2:38 NIV); (4) Godly sorrow brings repentance (metanoéō) that leads to salvation and leaves no regret, whereas worldly sorrow brings death. (2 Corinthians 7:10 NIV) – implies a journey; (5) The letters to the Seven Churches (Rev 1-3) call people to repentance (metanoéō) using the OT model of turning from a destructive lifestyle to a godly one. ↩︎

- Acts 15:7-11 NIV ↩︎

- Augustine, (s.)Sermons, trans. Edmund Hill, in The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century, ed. John E. Rotelle, part 3, vols. 1–11, 1990, s. 16A.9 ↩︎

- Augustine, however, also recognized the value of a conversion event and wrote of his experience, “I wanted to read no further, nor did I need to. For instantly, as the sentence ended, there was infused in my heart something light the light of full certainty and all the gloom of doubt vanished away.” (Augustine, Confessions 8—Article by Sandra Sweeny Silver) ↩︎

- Heidelberg Catechism, 88-90 – Conversion is the dying of the old man (mortification) and making alive the new (vivification). Or “heartfelt sorrow for sin, causing us to hate it and turn from it always more and more” and “heartfelt joy in God through Christ, causing us to take delight in living according to the will of God in all good works” ↩︎

- Westminster Confession of Faith, 9.3 – By Adam’s fall into sin, nature is unable “to do any spiritual good.” Fallen sinners are unable to convert themselves. It is God who “converts a sinner” and “translates him into a state of grace” thereby freeing him from his “natural bondage under sin…by grace alone” and “enables him freely to will and to do that which is spiritually good.” Because of our remaining corruption in this life we are never perfectly converted ↩︎

- John Williamson Nevin, The Anxious Bench (1845; Chambersburg, PA: Weekly Messenger), 52–53, Kindle edition ↩︎